Are school choice students just insufferable rich kids?

There are a lot of rich kids in public schools!

One of the principles of comedy is to “punch up,” and to not “punch down.” It’s easier to laugh at people in advantageous positions, while poking fun at people without as much power as you is more likely to be seen as bullying. You see this principle applied in political commentary as well, regardless of what side of the aisle you’re looking at.

When it comes to anti-school choice material, much recent criticism has focused on the identities of choice program participants.

When all programs were targeted to low-income kids (more on what this means in a moment) or students with disabilities, you didn’t see a lot of people arguing about children “deserving” to participate. We saw a lot of arguments about whether programs were effective or whether the benefits were worth the costs. But wealthy kids? Those are easier targets.

To be fair, there’s definitely something that sounds unappealing about “welfare program the wealthy,” as some critics have recently framed universal school choice programs.

But America has been incredibly comfortable with using taxpayer dollars to pay for the education of wealthy kids. In Chicago, where I grew up, the poster child for this situation was New Trier, where the median income is $250,000 and the public high school spends a whopping $42,000 on each student. As you might expect, demand for this school was very high and so were surrounding housing prices. If a comedian decided to pick on a New Trier high school student, he’d have no choice but to “punch up.”

So it’s not “rich kids get their parents’ top choice of education paid for by the government” that concerns us. If I’m being charitable, when I see criticism of universal programs making all students eligible, I think the underlying assumption is that disadvantaged students will get pushed out. If that were to happen, then we’d truly have a “welfare program for the wealthy.”

Fortunately, this assumption is empirically testable. Either low-income students are participating in programs with universal eligibility, or they aren’t. Unfortunately, it’s hard to get the data necessary for that testing. One program that has expanded from targeted eligibility to universal eligibility (well, nearly so at 98%) publicly reports data about the household incomes of participating students: Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program (CSP).

When the CSP was established in 2011, it was restricted to children from households making less than 150% of the threshold for the free and reduced-price lunch program (FRPL), which was $61,000 for a family of four at the time. More specifically, you got 90% of the state per-pupil aid dedicated to your education if you came from a household making 100% or less than the FRPL threshold ($45,000 for a family of four at the time), and if your household made between 100% and 150%, you received 50% of the money. In 2013, Indiana expanded these income thresholds to 150% and 200%, respectively, along with adding pathways for siblings, special education students, and students assigned to public schools with the state’s worst accountability rating. In 2022, Indiana raised the eligibility threshold to 400% of FRPL, $220,000 for a family of four at the time. They’ve continued to make minor adjustments since.

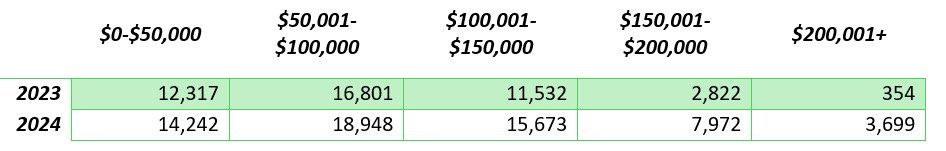

Below is the enrollment by income data in the Indiana Department of Education’s most recent report on the CSP. For some perspective, in 2024, a family of four in the $50,001-$100,000 bracket is under the 200% FRPL threshold.

There’s a lot more to unpack here than a Substack post has time for. But the main takeaway I have is that when there is a societal movement toward participating in the CSP—such as a pandemic or prominent news coverage—low-income families also seem to benefit. Based on these counts, 44% of participants are “low-income” as the state has traditionally defined it.

I’m not going to pretend that this is a slam dunk for pro-school choice folks. Maybe the low-income numbers seem too low or the top income numbers seem too high.

But maybe you’re surprised the low income figures jumped at all given traditional income-based awareness gaps in school choice programs. We might be seeing what the “diffusion of innovation” hypothesis predicts: Wealthier families participating in the program is facilitating marketing or public buzz that allows low-income families to learn about the program. We’ll know more in the coming years.

It is also worth noting that CSP participation was stagnating by the time COVID came around, and the pandemic that led to a new interest in universal eligibility coincided with rising participation numbers among legacy “low-income” families as well.

And let’s not lose sight of the fact that there are several school districts in Indiana with healthy family income figures, as well. The Zionsville (median family income $195,714), Carmel (median family income $176,311), Hamilton Southeastern (median family income $147,564), and Noblesville (median family income $139,171) school districts enroll more than 55,000 students between them. No one is calling these districts “welfare for the wealthy.”

Regardless, if we look at the public evidence we have at the moment, a school choice program with universal eligibility can—and does—serve low-income families. And we shouldn’t be surprised, given how dozens of school choice programs directly targeting low-income kids have existed for many years, serving hundreds of thousands of students along the way. For now, even if you think more emphasis should be placed on helping disadvantaged students, the rich kid stereotype—the straw man that’s easier to punch up at—should be shelved.